Curriculum matters, but curriculum design is relentless. We talk about high expectations, joined-up planning, and equity for all pupils. Yet the process of building that curriculum, the actual work, is often squeezed into evenings, INSETs and weekend brain dumps.

One or two teachers are tasked with trying to build the whole thing. Schemes are tweaked or dropped, deadlines pass, staff lose clarity. Pupils feel it. The truth? Most leaders are trying to build the plane mid-flight.

We speak to hundreds of leaders each year and we see the same thing: schools know their curriculum needs work, but they underestimate what the job requires.

From our own experience, we estimate it takes over 900 hours to build a well-sequenced, high-quality English curriculum – complete with model texts, progression maps and implementation tools.

And that’s just the doing – writing, designing, annotating, resourcing, supporting. Behind this sits hundreds more hours of thinking, reading, discussing, testing and refining. It’s not a side project. It’s a strategic undertaking.

Tinkering or reset?

At some point, modifying what you’ve got takes more energy than building afresh. As the new Writing Framework warns: “Tinkering with poorly designed curriculum frameworks can lead to more confusion, not less.”

That’s when leaders face the real choice: patch or reset?

Five essential insights

1. Start with a subject intent that actually drives decisions

The Writing Framework reminds us that subject leadership is about coherence and continuity. It’s not just documentation to hand to Ofsted. Too often, though, subject intent ends up as a statement, not a strategy.

If your intent is to develop clarity and control in writing, then your curriculum should reflect that in tangible ways: explicit work on sentences, regular rehearsal routines, opportunities to redraft.

Medium-term plans should be designed around that purpose, not simply tick off a list of genres. Strong intent shows up in classrooms – in what teachers model, what pupils practise and what’s prioritised in feedback.

2. Create visible progression in reading, writing and spoken language

Progression is more than a spreadsheet. It should be lived in lessons and visible in pupil work. The Writing Framework highlights the importance of progression in grammar, transcription, sentence control and writing for purpose – yet too many curriculums still hinge on text types or topics alone.

Ask yourself: What knowledge should build from Year 1 to Year 6, and how do we make that visible in lessons?

3. Focus on teacher subject knowledge, not just tasks

We often expect teachers to model rich, precise, purposeful writing. But do we equip them with the subject knowledge to do it confidently?

Strong writing instruction depends on strong grammar knowledge. That doesn’t mean turning teachers into grammarians – it means giving them the understanding they need to explain why choices matter.

The Writing Framework urges schools to strengthen “expertise in syntax, grammar and linguistic effect.” That’s about helping pupils write with clarity and control. Subject leaders can build this by:

- Providing annotated texts that explain effects, not just showcase them

- Using CPD to explore writing decisions, not just success criteria

- Encouraging “talk-aloud” modelling where teachers explain the why as well as the how

4. Oracy and sentence control aren’t extras – they’re curriculum glue

The Writing Framework calls for “oral rehearsal, live modelling and sentence-level instruction.” Yet these practices remain underused, especially in UKS2. The result? Pupils jump to writing before they’re ready – and end up struggling.

Oracy improves sentence fluency. Sentence control improves structure. Together, they provide the glue that holds a writing curriculum together. Leaders can make this practical and routine:

- Ask pupils to rehearse aloud before writing: “Say your idea three ways”

- Provide sentence stems with variation: “Although ___, ___”

Model revision live: “Let’s shorten this for impact”

When these routines become core strategies, not optional extras, pupils’ writing becomes more confident, fluent and deliberate.

5. Consistency comes from feedback, not complexity

The biggest driver of inconsistency isn’t weak planning. It’s mismatched expectations around feedback and quality. Your curriculum must link directly to formative feedback.

That means every unit should build in clear focus points for modelling, editing and reflection. Pupils should also revisit prior learning.

The Writing Framework puts it plainly: “Assessment should feed forward.” Without that loop, teaching becomes task-driven and learning evaporates.

How we can help

At Leading English we work alongside schools to:

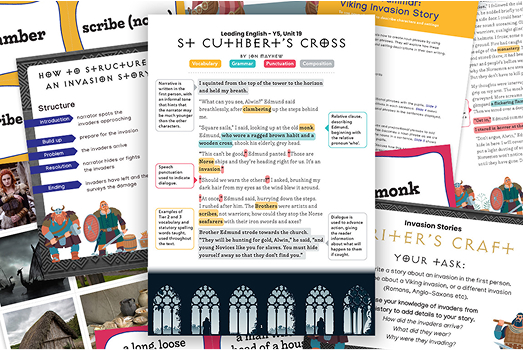

- bring clarity to subject intent and progression

- provide annotated model texts and planning tools

- embed routines for modelling, rehearsal and redrafting

- connect curriculum design directly to feedback and impact

- offer three consultancy visits a year, with ongoing planning calls and CPD support